Today, The Atlantic reminded me that Alan Greenspan, the renowned economist and former Fed chair, has been said to follow the Men’s Underwear Index (MUI) as an indicator of economic turning points. Many men consider new underwear a nicety, so when they feel economic belts getting tighty, they don’t go for new whities.

A much more serious indicator of hardship is auto loan delinquency. In the US, having a car is essential to keep a job, and people will forego many necessities, including new underwear, to pay off their wheels. In other words, increasing auto loan delinquencies is a major and late-stage flag that an economic winter is coming.

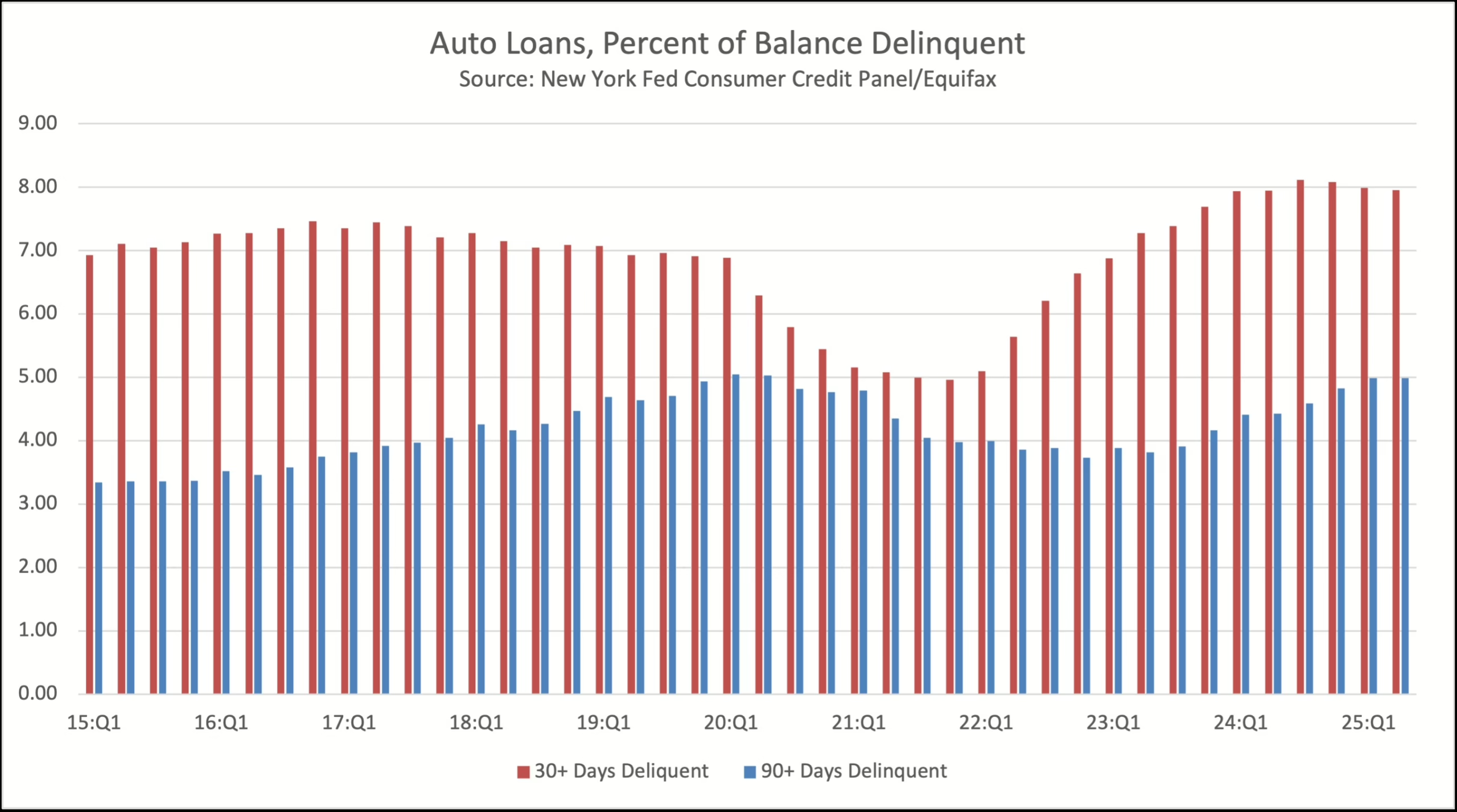

As you can see below from the latest Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, we are not there. Yet.

Auto loan delinquencies are slightly down, and those severely delinquent are stable.

But maybe that is because it has become harder to hear the (car) alarm.

In the last issue, The Risk Report mentioned that banks are increasingly transferring their credit risk to non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) to lower their capital requirements.

But such a synthetic risk transfer doesn’t lower the credit risk itself as much as it muffles the warning signs of something more systemic brewing.

And one of the most common loan types to originate outside banks is auto loans. While originations of car loans increased in the second quarter of 2025, the average credit score of borrowers decreased.

Specifically, subprime auto lending, where the borrower typically has a credit score of less than 620, is growing more rapidly than other types of auto lending, which is more of an omen than a glimmer of hope.

Another worrisome bleep was that a Texan subprime auto lender, Tricolor Holdings, collapsed and filed for liquidation in early September. Now, there have been allegations of fraud, and fraud tends to go on right until it doesn’t, which could explain the lender’s abrupt demise.

It is not, however, out of the realm of possibility that Tricolor’s borrowers also had difficulty in keeping up with their payments, and as an NBFI, Tricolor had less obligation to disclose and keep reserves for that.

Even worse, Tricolor was a significant issuer of asset-backed securities, meaning that it funded itself by packaging the subprime auto loans it had issued and selling those asset-backed securities (ABSs) to banks such as Fifth Third, JPMorgan Chase, and Barclays. Tricolor Holdings raised $1.4BN over 14 bond offerings in the past five years (source: Financial Times).

Those securities are now close to worthless and are being written off by the banks (source: Bloomberg).

Regitze Ladekarl, FRM, is FRG’s Director of Company Intelligence. She has 25-plus years of experience where finance meets technology.

This article is part of the FRG Risk Report, published weekly on the FRG blog. To read other entries of the Risk Report, visit frgrisk.com/category/risk-report/.